Those in the business of natural-resource protection know that it’s a complicated bag of tricks, fraught with difficult decisions during the process of achieving “balance” among the interests of many, often competing groups. In Virginia, as across the U.S., you have the expertise of local, regional, state, and federal governments at your fingertips. There truly is a wealth of information in print and electronically available to anyone who wants to be educated about natural-resource management in this country.

The following listing provides a rough sketch of government agencies and programs in Virginia with special focus on land and water concerns.

U.S. Government

The primary federal agency involved in land-resource management is the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). The agency was originally established as the Soil Conservation Service in response to the dustbowl phenomenon of the 1930s. Since that time, it has evolved into a dominant natural-resource agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The NRCS administers agricultural programs at the local level along with Soil and Water Conservation Districts.

The most visible programs administered by the NRCS are those associated with farm bills, which link crop-loss insurance benefits for farmers to conservation compliance.

NRCS provides technical assistance, cost-share funds, and oversight and supervision of conservation compliance through farm planning. A lesser-known program is the Conservation Reserve Program, which pays farmers to remove from production cropland on steeply sloped or highly erodible soils and replace cash crops with a permanent vegetative cover of grass or trees. All of these programs are voluntary. Fortunately, financial incentives and other “carrots” have made them quite successful.

The role of the NRCS is changing, as are the roles of many service agencies within USDA. Services in the future may be scaled back as the NRCS is faced with providing technical support and knowledge to an increasingly non-agricultural public. But there are still plenty of farms and fields on the Northern Neck.

Bay Program

The workings of the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) are complex and intricate, connecting all sorts of public and private interests. What’s important to note is that individual commitment is key to maintaining the good health of the bay, and the folks involved in the effort want your help.

In the Commonwealth, the departments of Conservation and Recreation, Environmental Quality, and the Chesapeake Bay Local Assistance Department handle Chesapeake Bay Program matters. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is the primary federal agency involved. The most contentious management issue today is non-point source pollution—that is, the pollution washing over the land and into waterways from hard-to-pinpoint sources.

Like the NRCS, the Chesapeake Bay Program also provides technical assistance and cost-share money through Soil and Water Conservation districts for compliance and for its suite of voluntary programs. Farmers, for example, have the ability to use CBP cost-share dollars to help them meet NRCS compliance. Most importantly, the programs save soil and increase farm profits through good resource management. The programs were designed to promote participation and increase the odds of success of a voluntary approach.

Virginia’s Coastal Program

Virginia’s Coastal Program, as it’s officially called, is actually another conservation partnership of federal, state, and local players. It is a network of all the state agencies and Tidewater communities, led by the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), that deal with coastal zone management. Because Virginia has laws and regulations to protect wetlands, underwater lands, sand dunes, fisheries, coastal water and air quality, and other sensitive coastal habitats, DEQ receives money from the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to coordinate and develop coastal policies and undertake all sorts of coastal projects. Research on oysters and birds, beach design, water quality, nature-tourism activities, fishing piers, plantings for public lands, and outright purchase of coastal land are among the many projects that have received help.

If you have an idea for a coastal project on the Neck or need help with a coastal management issue, call the Coastal Program at DEQ. Grants are usually given only to government entities, so if you’re with a private organization, be sure to work through your county planning office, the Northern Neck Planning District Commission, or a state agency.

Planning District Commissions

Planning District Commissions (PDCs) were created to provide consolidated regional services to counties and metropolitan communities. They are advisory bodies that furnish important data and trends to both localities and the Commonwealth. Planning district commissions can advise a county on how it can prosper by cooperating in regional projects—in the fields of transportation, land use, or community development, for example. As part of its regional mission, it often becomes a “testing ground” for new technologies or serves as a regional arbiter for shared resources. The PDC should be your first phone call if you’re seeking data of a regional nature: economic forecasts, census information, geographic information systems in place, or population-trends forecasting.

The Northern Neck Planning District Commission (NNPDC) is one of 21 planning district commissions in Virginia. The NNPDC provides planning, economic development, community development, and housing services to Westmoreland, Northumberland, Richmond, and Lancaster Counties, and to the Northern Neck’s six incorporated towns. The NNPDC’s commissioners include elected officials and citizens appointed by local governments. With funding from the Virginia Coastal Resources Management Program and the Chesapeake Bay Local Assistance Department, the NNPDC offers technical assistance to manage coastal resources and help localities implement the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act.

Soil & Water Conservation Districts

Like the NRCS, Soil and Water Conservation Districts (SWCDs) administer many local Chesapeake Bay programs. SWCDs are grassroots political bodies that run their programs under the guidance of locally elected district directors who volunteer their time. SWCDs have their own staff, are funded by state and local jurisdictions, and receive facility and equipment support from the NRCS. In this heavily cropped and forested region, SWCDs play an important role in both formulating and implementing natural-resource protection strategies.

SWCDs have staffers available to help farmers as well as homeowners to answer questions associated with preventing polluted runoff. In particular, county governments look to the SWCDs to oversee compliance for construction-related runoff on disturbed land, forestry and farming operations, storm water management, and water pollution. SWCDs also help landowners meet the agricultural provisions of the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act. If you come across a fish kill, an oil spill, a mud slick, or other pollution mess, call the Northern Neck Soil and Water Conservation District.

The Bay Act

The Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act, or Bay Act, represents the most significant legislation enacted to protect sensitive land and water resources.

Intent of the Law

The Bay Act aims at getting a stranglehold on that elusive monster—non-point source pollution. The Act has two important paths to achieve this: 1) by preventing the addition of non-point source pollution during land development activities; and 2) by reducing non-point source pollution that occurs during redevelopment activities. The Act aims to protect and manage all land critical to the protection of water quality in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. By definition, tidal shores, tidal wetlands, certain non-tidal wetlands, floodplains, steep slopes, highly permeable soils, and highly erodible soils are among the lands to be managed and protected.

Preservation Areas

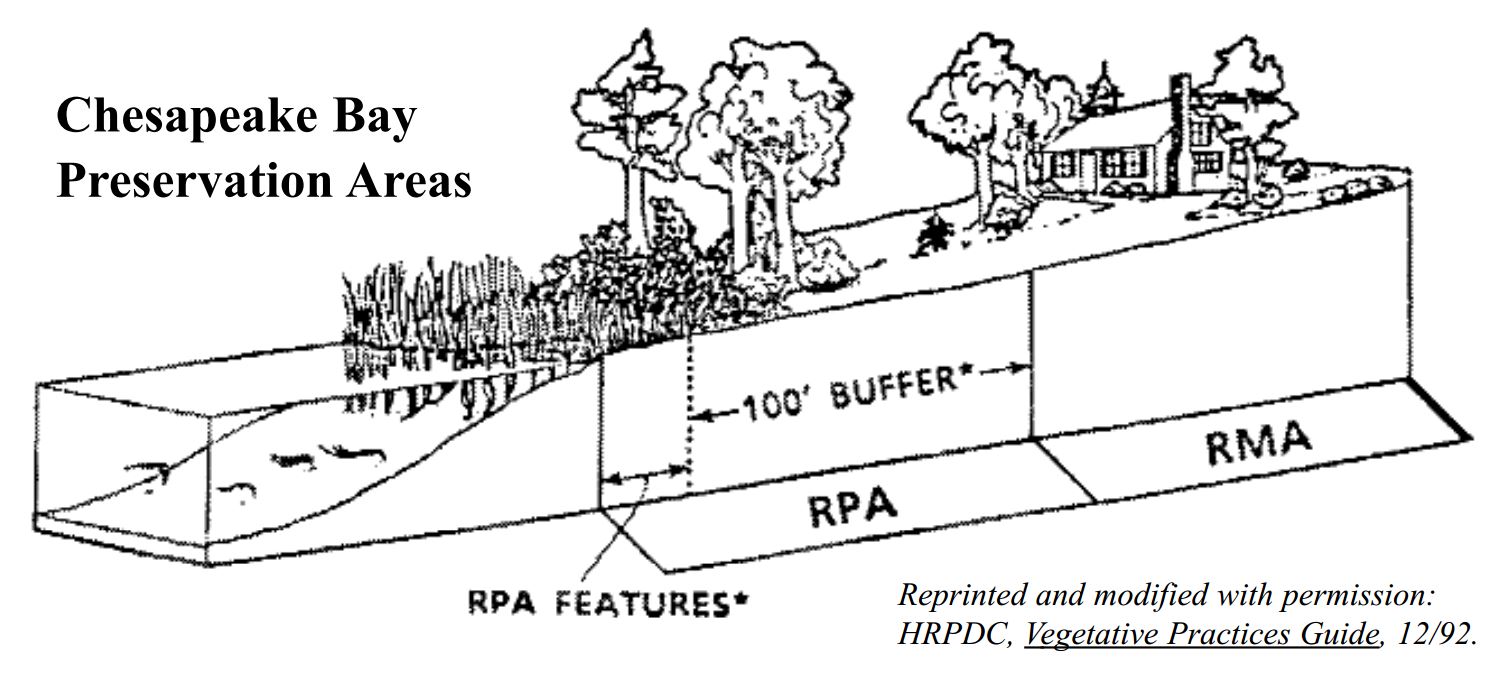

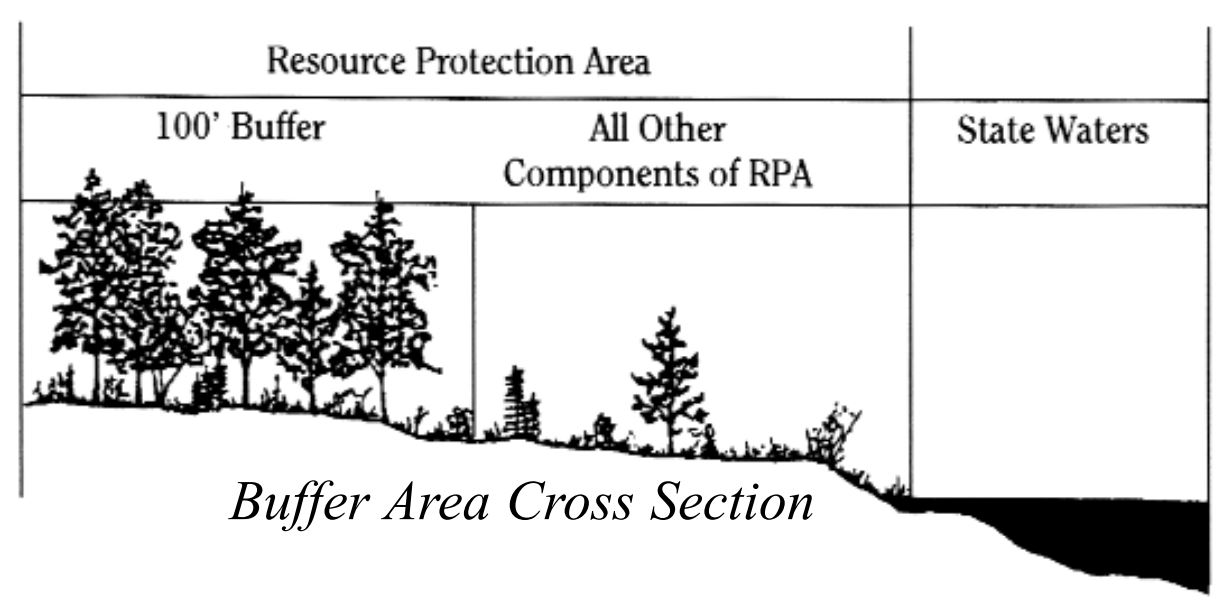

Preservation areas include Resource Protection Areas (RPAs) and Resource Management Areas (RMAs). The RPA consists of all ecologically sensitive features—tidal shores, tidal wetlands, and non-tidal wetlands adjacent to tidal shores, tidal wetlands, and tributary streams. The RPA includes a 100-foot buffer landward of these features. Considered the “last barrier” to runoff before it reaches surface waters, the buffer is intended to slow runoff, prevent erosion, and filter non-point pollution. Generally, only water-dependent uses such as piers, or restoration of existing structures, are allowed here.

Resource Management Areas provide additional water quality protection and guard the environmentally sensitive features of the RPA. The size of RMAs is determined by each county or town and may vary in width from several hundred feet to all of the land within a county not already in an RPA.

Throughout the Tidewater region, counties and towns protect sensitive lands using a suite of management tools. On the Northern Neck, all four counties have extended the RMA designation to the entire county, providing the maximum protection to surface waters under the guidance of the Bay Act. Land clearing and construction activities normally allowed by local zoning ordinances are allowed in RMAs by carefully following county-specific practices.

Nuts & Bolts

The Bay Act establishes the general definition of preservation areas and recommended practices within them. Your county or town, however, determines actual activities allowed within these areas. Most likely, a land-use planner will work with you directly to protect and enhance your property value through “best management practices.” These BMPs, as they’ve been called among farmers for years, are specifically designed to reduce the impact of raindrops on your land (which is especially important during clearing and construction), to slow overland water flow with its associated problematic runoff, and to promote the absorption of nutrients and pesticides before they reach protected waters.

As part of their commitment to good water quality, farmers in the region have been setting aside vegetated filter strips and employing other soil-conserving tactics. The shift of focus on BMPs for residential and commercial properties has allowed Northern Neck counties to have a better handle on environmental protection as the region develops.

BMPs are spelled out in Vegetative Practices Guide, a handbook published by the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission. Here is a list adapted from it.

As part of your site plan review, your county or town may ask you to do the following:

1) Preserve existing vegetation. It is cheaper to leave existing vegetation than to try to reestablish it.

2) Add to and enhance vegetative buffer areas. By planting a variety of ground covers, shrubs, and trees, you will maximize the ground’s ability to remove pollutants. (See “BayScaping.”)

3) If appropriate, add to and enhance vegetative filter strips—areas specifically designed and planted to accept the runoff from upland development. These work best on slopes of five percent or less.

4) Consider grassed swales. Used with other practices, grassed swales help reduce the velocity of runoff and allow some infiltration of water. Remember to keep the grass thick and high and minimize (or even better, eliminate) the use of fertilizers and pesticides.

5) Plant trees, shrubs, and other woody vegetation. The most significant reductions in runoff occur in wooded and heavily vegetated areas with a dense understory. Other benefits include the creation of wildlife habitat, natural absorption of pollutants, and erosion control. And, once established, these areas require little maintenance.

6) Create a shallow marsh. These are shallow pools suitable for marsh plants. Their use will be limited to soils with slower infiltration rates, but so far they have proved very good at removing nutrients and other kinds of pollutants through the processes of plant uptake, retention, and settling.

7) Reduce impervious surfaces. There are lots of alternative surfaces that will allow water to permeate underlying soil: brick on sand, well placed stepping stones with grass strips in between, and wood decking.

8) Limit land disturbances. Of course, this is the ideal solution. Evaluate your needs and limit intrusions wherever possible.

The Bay Act also addresses septic tank maintenance. Throughout many areas of the Northern Neck, where sandy soils predominate, proper maintenance of septic tanks is critical to the integrity of ground and surface waters and, of course, the health of area residents and wildlife. The law requires that tanks be cleaned out at least once every five years. Houses built after passage of the Act are required to set aside a reserve septic drain field, able to handle the treatment capacity of the primary drain field. The reserve drain field cannot be built upon.

Talk to your county planner or building inspector about site-specific questions.

The 100-Foot Buffer

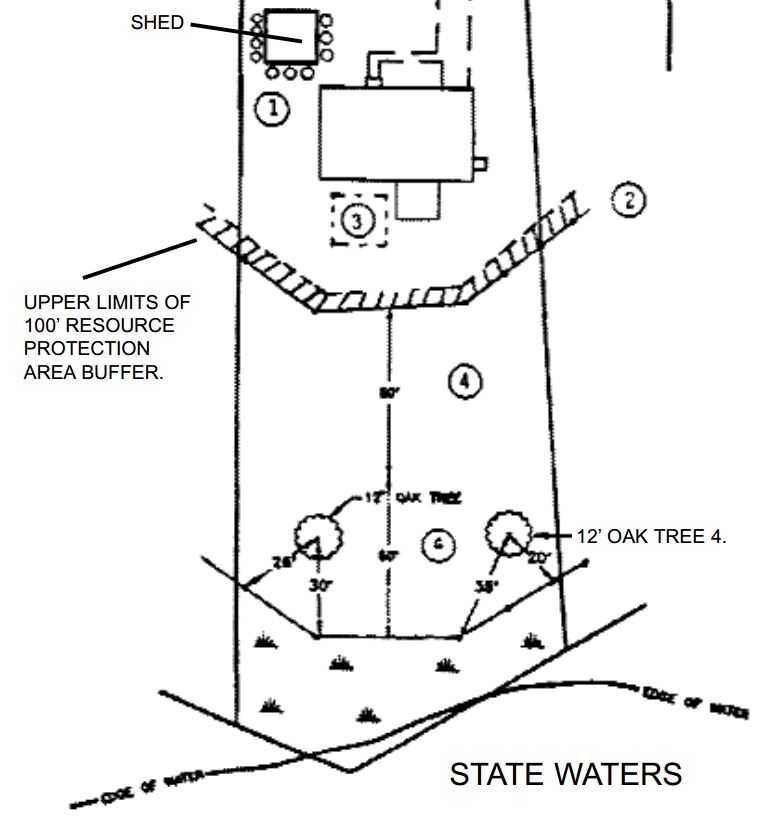

When building a new structure on your property, your first step is to closely evaluate the area beyond the required 100-foot protective buffer. The smallest amount of land possible should be disturbed. There are also four primary activities you can use to compensate for the impacts that you are introducing. (Numbers below refer to the circled numbers cited in this drawing.)

1) Place plants in a mulch bed on the downstream sides of the building in order to slow down the associated roof runoff from it, eliminating the added impacts to the lot.

2) Calculate the total square footage of the roof and add that square footage to the upper limits of the buffer, thereby protecting an equivalent area of land according to the limited activities that are appropriate for the site.

3) Plant a large shrub bed (the same size as the structure’s roof) to intercept previously unmanaged runoff from the house, and divert the runoff to the shrub bed.

4) Add vegetation in the form of small trees and shrubs in the lower limits of the buffer area to add filtration quality and nutrient uptake potential for the total site.

Help Shape the Region’s Economic Future

Virginia’s Coastal Program on the Northern Neck has provided support for mapping projects and much needed staff positions for wetlands education and protection and local planning initiatives. It has also worked to boost environmentally compatible economic development in both the Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula.

The goal is to produce a strategy-implementation plan, crafted by the community after a series of public “visioning” sessions. The strategy might include recruiting “zero”-emissions manufacturers or nature-tourism companies and improving the economic and environmental efficiency of existing businesses.

A vibrant economy depends upon active participation from the community to accurately identify resources and shape a strategy for the future. Call the Northern Neck Planning District Commission for more information about how you can get involved.