Northern Neck farmers have wrestled with soils that are a mixture of sands and loams for centuries. That they have been commercially successful is largely due to clever management, regular applications of fertilizers and water, and a benevolent climate, rather than the quality of the soil itself. Understandably, years of wind and water energy, along with a growing dependence on chemicals for higher yields, have taken their toll on the peninsula’s farmlands, creeks, and all kinds of water and land-based fauna. Farmers who learned to cope with poor soils are now challenged to eke out more from the land with fewer chemicals and synthetics. Modern-day gardeners will surely have a tough go of it, too.

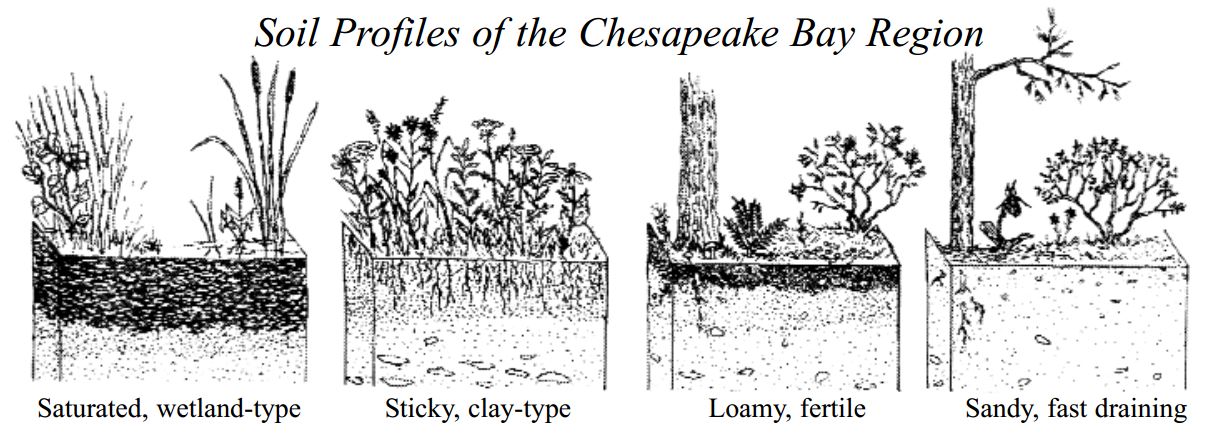

As every good gardening book emphasizes, it all starts with the soil. To find out which types of soil cover your property, you might begin by conducting a soil test over several areas of your yard. To get a better idea of your soil’s composition, however, visit your county extension office. The staff in these offices will gladly show you the soils maps and help you interpret what you find.

Getting Acclimated

Virginia’s Northern Neck provides plenty of opportunities for you to hike outdoors and make connections between natural features and the soils under your feet. Both the Westmoreland and Belle Isle State Parks provide good examples of the beach-to-upland habitats typical of the entire region.

Take a walk along the Big Meadows Trail in Westmoreland State Park and stop for a minute to study the interpretive information in the trail brochure. Here, in less than a mile, you will see evidence of where white-tailed deer have been feeding on young seedlings and saplings of the upland forest, and where industrious beavers have recently taken down a young tree in the lower reaches for a community dam project.

The watchtower provides a magnificent, bird’s-eye view of Yellow Swamp, completely filled-in with wild rice during early fall, fanning its top feathers in the breeze. Or visit the Hughlett Point Natural Area Preserve on the Bay in Northumberland County, where coastal forces eliminate all but the hardiest shrubs and grasses able to withstand strong winds.

The above is just a brief sketch, of course. There are available several field guides to help you fully enjoy the sights, sounds, and smells found in these natural theaters. A general recognition of plant communities will go a long way toward understanding the native vegetation and wildlife that surround your house. And once you’ve taken time to learn about the plants and trees and underwater grasses, and all the creatures that live within them, you will have unlocked the real treasures to be found here.

Closer to Home

But what does all this have to do with your yard? Well, knowing soil attributes will help you in planning landscape work or trying to establish flower and vegetable gardens. If you live in low elevations close to the water, you might be dealing with a less permeable, loamy soil that doesn’t tolerate deep-rooted plants and occasionally ponds up during rainy seasons.

Or it may be a fast-draining soil that does not retain water and is highly susceptible to erosion from wind and water. If you have highly acidic pine needles or oak leaves lying around, it’s a sure bet it will need a good dose of lime—unless you’re limiting your plantings to acid-loving camellias and azaleas. Since the original topsoil was probably stripped or otherwise lost long ago, the most important thing you can do for your soil is add organic material.

Though you might feel tempted to import topsoil for small garden plots, it’s probably a bad idea. Since sand is the primary component of the Northern Neck’s soil profile, the heavier, added topsoil will eventually sink down through the soil column.

A better approach: add organic matter—humus and peat—and lots of it. Since you’re living in the middle of farm country, a cheap (and maybe free) truckload of manure is only a farmer away. Talk to your neighbors and your county extension agent for help in locating a farmer if you don’t know one. Be sure to specify aged manure, and be aware that it may contain grass and other seeds. Many farmers and horse owners will give away manure just to make room for next year’s piles.

If you can’t find a convenient, ready supply of manure, home composting is a good alternative.

In areas planned for or planted in grass, you will face some difficult management choices. A better idea might be to get rid of it altogether. Grass, by nature, demands lots of nutrients and a regular diet of water—both of which can be in short supply during droughts.

If you find the competing, native wiregrass as difficult to manage, you may decide to limit your “improved” lawn to high-traffic and recreation areas. Again, the county extension agent can help you determine the right seed mix and maintenance program for your property.

Because you live in a low-lying area with soils subject to erosion, keeping your land covered is of critical importance to the future health of nearby waterways. Bare spots and areas planned for future plantings should be mulched or temporarily planted in ground cover or grass to stabilize the soil and keep it on your property. See the “BayScaping” chapter for a list of ground covers that do well in this region.

Because you live in a low-lying area with soils subject to erosion, keeping your land covered is of critical importance to the future health of nearby waterways. Bare spots and areas planned for future plantings should be mulched or temporarily planted in ground cover or grass to stabilize the soil and keep it on your property. See the “BayScaping” chapter for a list of ground covers that do well in this region.

Whether you live along Lancaster Creek or in downtown Reedville, you are surely aware that your soil’s ability to hold water and slowly release it into underlying aquifers—a process commonly called percolation, or perc—is marginal at best. Throughout most of the Northern Neck, water moves quickly through the upper sand layers, hits underlying clay soils, and moves rapidly in a lateral fashion into ground and surface waters. Eventually, it mixes with larger creeks making their way to the Bay. Fast-percolating soils present a challenge to groundwater quality. They are a genuine concern to anyone responsible for enforcing septic-system regulations.

The “Invisible” Water

Most people don’t give it much thought. But every minute, under the earth’s continents, water moves below our feet. Inching its way between layers of solidified (or consolidated) rock, or flowing with a bit more ease between looser rock formations (unconsolidated), this groundwater moves and ultimately mixes with surface waters—rivers and oceans.

Throughout the country, groundwater is usually one source of a community’s drinking water supply.

Other freshwater sources include reservoirs and lakes. On Virginia’s Northern Neck, the latter sources don’t exist, and groundwater is the sole source of drinking water. Much of it moves through the Columbia Aquifer and the older Yorktown Eastover Aquifer formed millions of years ago. It is accessed through conventional wells or artesian wells, those that tap into water that is confined and under pressure.

Because groundwater serves all municipal and industrial freshwater uses here, it has been studied intensely by natural-resource planners, hydrogeologists, and researchers both on the Neck and across the state.

One thing that’s been learned, though often hotly debated among different users of the land, is that traces of whatever ills are dumped on the ground can and do find their way, eventually, into underground aquifers. Another discovery: where groundwater use exceeds its ability to replenish itself (which on the Northern Neck happens mostly by rainfall), aquifers become more susceptible to the intrusion of underlying saltwater.

You can take specific steps to protect the Northern Neck’s water supply:

- Be aware that whatever gets sprayed or poured onto the ground and into the soil—in the form of a pesticide application, or spilled motor oil, or a leaking septic tank, for example—can sooner or later reach our groundwater.

- Keep your septic tank in good condition by cleaning it out at least once every five years. This will rid the tank of stubborn solids that don’t break down, minimizing the risk of contaminating underground aquifers.

- Always use a drop cloth for outdoor projects, especially when adding or changing fluids in your car.

- Reduce the use of toxins, both inside your home and outdoors, in lawn and garden areas.

- Have your well tested regularly.