Have you ever gone for a Sunday afternoon drive to explore the surprises that await you down a narrow lane? Perhaps you will see a rolling meadow with horses grazing behind a fence, or a sweeping reach of freshly cut field, dotted with rolled hay bales. Then you come across a new subdivision. Glitzy three-story homes with stately columns guard the beveled glass front doors, and freshly-tarred driveways lead to two-car garages. And, as far as your eyes can see, sparkling green grasses—mowed to within two inches of their lives—sweep around tightly planted shrub beds that hug the houses in perfect symmetry. Not a blade out of place or a flower drooping.

The lawn tradition originated in England and has endured for nearly 400 years. Looking to the future, it may be time to challenge some long-held traditions and reflect upon life’s busy pace and demanding schedules in making landscape choices. Lawns require a tremendous commitment of manpower (both for initial planting and regular maintenance) and abundant amounts of nutrients and water to sustain them.

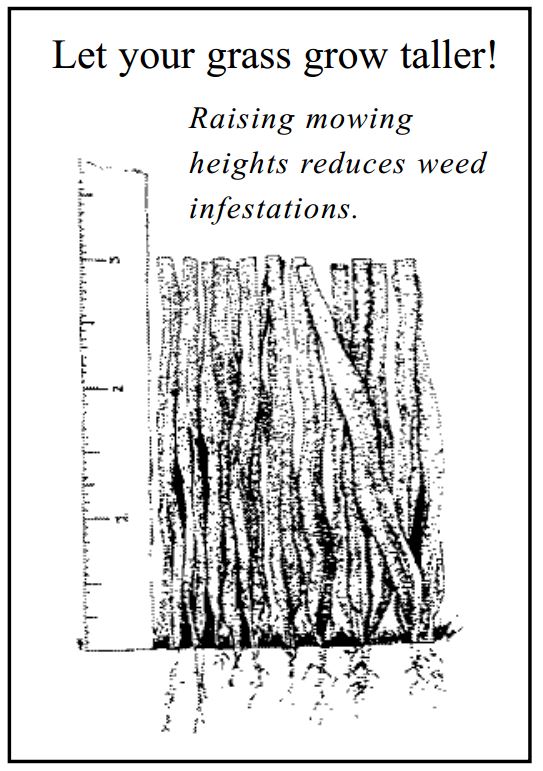

Of course, the stately, velvet-green, weed-free lawns that you come across (most often in new subdivisions) are amply doted upon by dedicated lawn aficionados. But these green carpets come at a high price. The price is paid by creeks, streams, and waters of the Bay, which face a challenge in the form of surplus nutrients—much of which originate in upland lawn and garden areas. Throughout the Bay’s watershed, an attitude adjustment may well be called for. It might be okay to let a few weeds live alongside the cool-season fescue grasses or warm-season Bermudas.

While contemplating some weed flexibility, you might also ask yourself how much lawn you really need. A landscape ethic originated in water-stingy communities out west is taking hold all across the country. People are creating lawns out of different things: herbaceous vines and groundcovers, ornamental grasses, and grand sweeps of interplanted perennials and herbs with grass walkways. Areas once exclusively in turf are taking on a new personality, reminiscent of the old victory garden, and the once ostracized weed has been elevated to a new status. Herbicides, once the backbone of weed control, are increasingly being passed over by concerned parents and pet owners for a solution of a different stripe—IPM, or integrated pest management—which is finding its way into many communities. (See “Pesticides.”)

The movement toward lawn alternatives offers an interesting visual change for home landscapes and, more importantly, creates new shelters and feeding places for animals during a time when such places are desperately needed. Indeed, the new American lawn may turn out to be no lawn at all.

Attracting Wildlife to Your Yard

You can provide food and cover for area wildlife in a number of simple ways:

You can provide food and cover for area wildlife in a number of simple ways:

- Plant trees, shrubs, and groundcovers. Creating natural corridors of vegetation provides birds and small mammals with places to rest, hide, and raise their young. Hedgerows, wildflower meadows, and brush piles also make good resting and nesting sites.

- Enhance wildlife food sources by planting native trees, shrubs, and flowers that provide berries, nuts, and seeds. Refer to the “BayScaping” chapter for ideas.

- Provide water at different heights in your home landscape for drinking and bathing: plant cup-shaped flowers for insects, and place shallow lids and dishes out for birds and small animals. Remember to add fresh water regularly, especially during dry summer months, and place containers near cover for quick getaways.

- Replace open lawn areas with wildflower meadows to draw butterflies, bees, and other insects needed for pollination.

- Create a small water garden, complete with a water-lily tub or water barrel, for birds, small fish, and perhaps a frog or two.